The ACL (Anterior cruciate Ligament) is one of 10 most common injury sites in athletes. In this blog, we will discuss the various abnormal running mechanics that disposes an athlete to an ACL injury. Further, we will also elaborate on the running mechanics seen after and during recovery from an ACL injury.

ACL injuries can range from a minor sprain to a complete tear. Between the choice of managing it surgically or conservatively, clinicians as well as athletes most often choose a surgical management which largely involves reconstruction due to evidence and anecdotes showing a faster return to sport and more overall positive outcomes [1,2]

Post an ACL reconstruction, a return to running, as early as even 6-8 weeks, is an important benchmark for a successful return to sport. Due to the nature of this injury, a myriad of biomechanical changes (kinematic, kinetic and muscle changes) are observed during different return to sport stages that lead to inappropriate loading on the ligament and surrounding structures, thereby increasing the risk of future knee issues.

Hence, it is essential to know the specific biomechanical alterations that occur post an ACL reconstruction to restore safe movement patterns and reduce the chances of long term disability.

Can abnormal running mechanics lead to ACL injury?

The ACL, being one of the major ligaments in the knee, has many important functions, the most crucial one being providing stability by preventing excessive forward movement of the tibia (shin bone) relative to the femur (thigh bone). ACL injuries during running can occur due to a combination of biomechanical factors, improper movement patterns, and external forces.

- Sudden Deceleration or Change in Direction

Stopping or changing direction abruptly while running at high speed. Twisting motions can place a huge stress on the ACL.

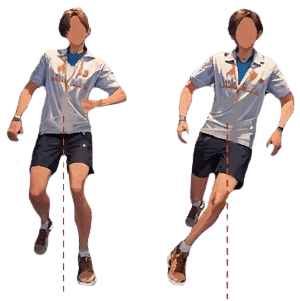

- Dynamic Valgus Collapse

Due to an improper alignment or muscle imbalances, when the hip, knee, and ankle are not properly aligned, and the knee moves inward (valgus) more than recommended ranges instead of maintaining proper alignment.

This misalignment places increased stress on the ACL, making it more susceptible to injury.

- Overstriding

Overstriding, or landing with the foot too far in front of the body, can increase the load on the knee joint due to the leg being in a less favorable position to absorb and dissipate the forces generated during ground contact, leading to increased strain on the ACL.

- Terrain and Surface Conditions

The running surface and terrain plays a major role. Uneven surfaces, sudden changes in elevation, or slippery conditions can increase the risk of missteps and awkward landings, potentially leading to ACL injury.

- Poor Landing Mechanics

Improper landing mechanics, such as landing with a straight knee and limited flexion, can increase the risk of ACL injury. A lack of proper shock absorption during the landing phase can transmit excessive forces to the knee joint, potentially causing injury to the ACL.

Now, we will discuss the detailed criteria to permit an athlete to return to running.

Criteria for return to running – [3]

- Time Based Criteria

Open Surgery with rehabilitation – 10 weeks

Arthroscopic surgery with rehabilitation – 12 weeks

Arthroscopic surgery with protective rehabilitation – 21 weeks

Open Surgery with protective rehabilitation – 29 weeks

- Clinical Criteria

- Range of Motion (ROM) – Full knee flexion ROM or 95% of ROM of non-injured knee. Full knee extension ROM

- Pain – < 2 on Visual Analogue Scale

- Ambulation – Full weight bearing ambulation

- No signs of effusion or graft “giving away”

- Performance based criteria

- Balance – Score on Y balance test – ≥90%

- Functional tests –

- Functional test Limb Symmetry Index(LSI) >70%

- Hop tests LSI ≥85%

Hop tests or vertical jump tests without criteria - Jog on a mini trampoline for 10min without problems

- 10 consecutive single-leg squats to 45° knee flexion without loss

of balance, and 30 steps-and-holds without loss of balance or excessive motion outside of the sagittal plane - Ability to perform single-limb functional exercises without pain or swelling

While this criterion seems to be exhaustive, the most important criterion would be time. There’s a large variable difference in the mechanical properties of the ligament at 10 versus 21 weeks.

The functional and clinical status may be dependent on the athlete’s status prior to the injury. A re-injury would present differently as compared to a first time injury.

Therefore, even after clearing the criteria, the athlete is susceptible to facing marked biomechanical changes to their running patterns as compared with their pre-injury status. The changes are reported as early as 3 months post-op, up to 5 years post op, with the most common changes being observed in the sagittal plane.

RUNNING MECHANICS AFTER ACL INJURY

The deviations are seen across kinematic, kinetic and muscle activation variables. [4]

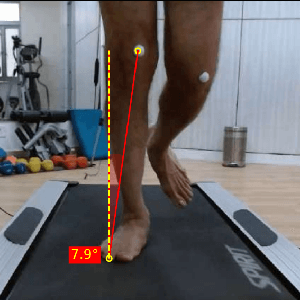

- Kinematic Changes

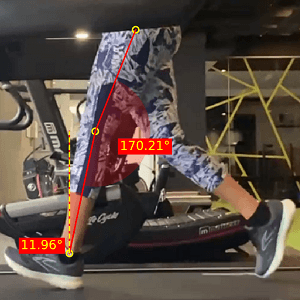

- A reduction in peak knee flexion angle at midstance as compared to non-injured limb. This deviation is seen more than 6 months post ACL reconstruction.

- A reduction in total knee flexion excursion throughout running is observed in the long term.

- Reduction in terminal knee extension

- Depending on clinical status, there may be reduced anterior knee translation and tibial medial rotation during downhill running.

The knee flexion reduction is the most significant deviation post ACL reconstruction. The potential causes are the surgical techniques employed which affect the stiffness of the reconstructed ligament, protective mechanisms in the short term, a psychological fear of re-injury, proprioceptive knee changes and an asymmetry in muscle strength of lower limbs.

- Kinetic Changes

- The peak internal knee extensor moment is reduced in the time duration of mid-term and long term recovery. This can be related to the knee extension deficit that often occurs post ACL injury. Hence it becomes essential to achieve terminal extension through rehabilitation

- Contact forces – An overall reduction in knee flexion excursion reduces contact forces between the tibio-femoral joint, while increasing the contact forces on the patella-femoral joint

- Vertical ground reaction forces – A change in ground reaction forces is dependent on the load distribution on both the limbs. Usually, the ground reaction and vertical forces acting on the knee joint usually present no long-term changes. Any changes are in the initial phases of rehab, which self-resolve over time.

- Muscle activation

- Increased vastus lateralis activity in the non-injured limb during a paced 10 minute endurance run.

- An asymmetry in the hamstring strength in the long term is usually not present, but in cases where it is, a greater lateral knee rotation at foot strike and peak knee lateral rotation during weight acceptance phase of running is present on the affected side.

Clinical Implications

The altered movement patterns observed port ACL reconstruction are probable causative factors of a future Knee OA and a re-injury. These altered movements do not appear to self-resolve over time, hence clinical interventions help in preventing a long term disability.

Since the sagittal plane kinematics are most affected, a 2-Dimensional Video Analysis can be an extremely useful tool to evaluate these altered movements in running gait.

Rehabilitation focus –

- Achieve a normal gait pattern before commencing with running

- Ensure full ROM of injured knee, comparable to the non-injured knee

- Focus on close to equal strength in both lower limbs

- Incorporate jump training with augmented body weight support to improve safe landing mechanics.

We hope that this blog helped you get a clear understanding of Running mechanics after an ACL injury.

Setting up your own gait analysis lab is now easier than ever. To learn more about GaitON’s running gait analysis modules, contact us today!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading our blogs everyday, and each week we bring you compelling content to help you treat your patients better. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — Team Auptimo

The information found within this site is for general information only and should not be treated as a substitute for professional advice from a licensed Physiotherapist. Any application of exercises and diagnostic tests suggested is at the reader’s sole discretion and risk.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

GAYATRI SURESH (PT)

Gayatri Suresh (PT) is a Biomechanist who has completed her B.P.Th from DES College of Physiotherapy and M.P.T (Biomechanics) from SRM College of Physiotherapy, SRMIST. Her field of clinical expertise is in movement assessments through video analysis. Apart from her work at Auptimo, she works as a Clinical Specialist at Rehabilitation Research and Device Development, IIT Madras. She has been conferred with gold medals for her Research presentations and for securing First rank with distinction in her MPT degree respectively

REFERENCES (Running mechanics after an ACL injury):

- Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 1, outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2008 Jan;36(1):40-7. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308190. Epub 2007 Oct 16. PMID: 17940141; PMCID: PMC2891099.

- Feucht MJ, Cotic M, Saier T, Minzlaff P, Plath JE, Imhoff AB, Hinterwimmer S. Patient expectations of primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016 Jan;24(1):201-7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3364-z. Epub 2014 Oct 2. PMID: 25274098.

- Rambaud AJM, Ardern CL, Thoreux P, et alCriteria for return to running after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a scoping reviewBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2018;52:1437-1444.

- Pairot-de-Fontenay, B., Willy, R.W., Elias, A.R.C. et al. Running Biomechanics in Individuals with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Sports Med 49, 1411–1424 (2019)

- Ektas, N., Scholes, C., Kulaga, S. et al. Recovery of knee extension and incidence of extension deficits following anterior cruciate ligament injury and treatment: a systematic review protocol. J Orthop Surg Res 14, 88 (2019)