With the increase of running-related injuries, clinicians need to formulate running-specific assessment plans for their patients. Furthermore, we will be discussing a standardized approach that you can use to integrate as a part of your assessment process. A running assessment is a step by step process including 4 stages:

• Comprehensive medical review & training history.

• A Physician Examination.

• A running gait analysis, if the runner is symptomatic and,

• Physical therapy consultation to propose programs for correcting biomechanical aberrations of running motion.

Medical & training history

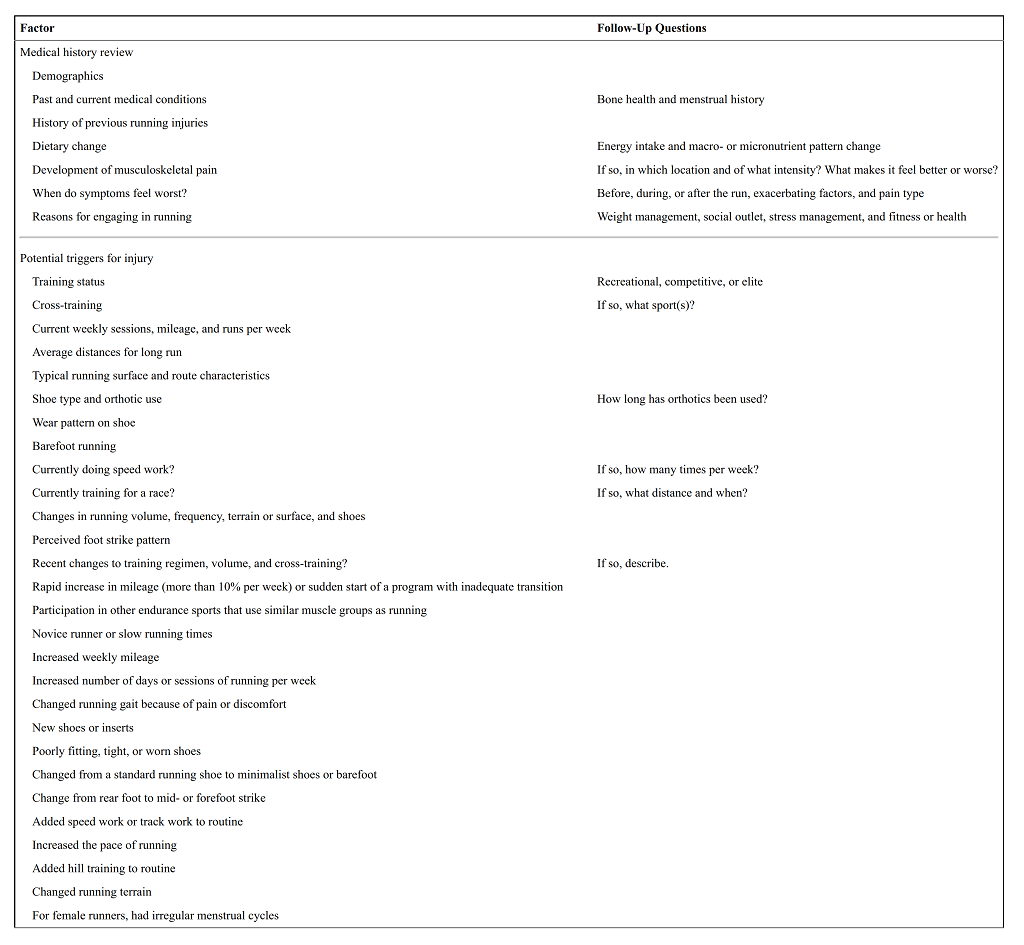

Medical, as well as training history documentation, is an excellent tool used by clinics for diagnosing running-related injuries in patients.

Here’s an effective ‘Runner intake questionnaire’ you can provide your patients at their first visit for assessing their running pattern & potential triggers for injury.

Clinical usage of the 'runner intake questionnaire'

A. RUNNING SURFACE & ROUTE CHARACTERISTICS

Undoubtedly, knowing about the running surface & route used by the patient can help you estimate the resulting joint and muscle loads, & identify aspects that may be associated with injury risk.

Surface | Injury |

Beveled Roads | When the foot lands on the lateral side of the road, the lower extremity is subjected to strain. |

Sand | Soft tissue injuries such as midportion Achilles tendinopathy |

Hills | Eccentric loading to knee extensors |

B. MILEAGE AND RUNS PER WEEK

Recreational runners with weekly volume <24 km/week or <3 years of training have a higher risk of developing leg pain.

Additionally, training for >7d/week (or >1 sessions/day) is considered as excessive. Also, Such high volumes don’t allow enough time for the soft and bony tissue recovery, moreover increasing the chances of injury. Studies have also shown that <2d/week of rest increases the risk of overuse injury by 5.2-fold!

C. SHOE MILEAGE & WEAR

D. FOOT STRIKE PATTERN

CONCLUSION

Although the documentation of medical and training history is very important, it is seldom used in isolation. Instead, it should act as a guiding criterion for subsequent examinations of the patient.

Once this step is complete, you can use this documentation for conducting a comprehensive physical and functional assessment of the patient.