“Your child has scoliosis; his spine is in a curved posture. It may affect the alignment of the shoulder and the pelvis in the future.”

“Foot pain could be because you have a flat foot, meaning you have flattened foot arches.”

“You’re sitting too slouched at work. Sitting straight will prevent back pain in the future.”

“Back pain seems to have caused your spine to shift to the opposite side of pain. I’ll give you exercises to bring your back to neutral alignment.”

“You’re placing your leg too far ahead when you’re running. Reducing your stride length will improve your running form and efficiency.”

Did you find a difference in how posture is described in each statement?

Posture is an extensively taught topic across undergraduate and post-graduate syllabi in Physiotherapy.

“Wrong posture”, “Incorrect alignment”, and “Muscle Imbalances” are common diagnoses for patients with pain.

Although, what does one describe when they talk about posture?

Does it mean the structural alignment of the body or a person’s preferred comfortable posture? Does it refer to a compensatory posture that has occurred due to pain or injury? Or a dynamic movement?

Can we describe them interchangeably?

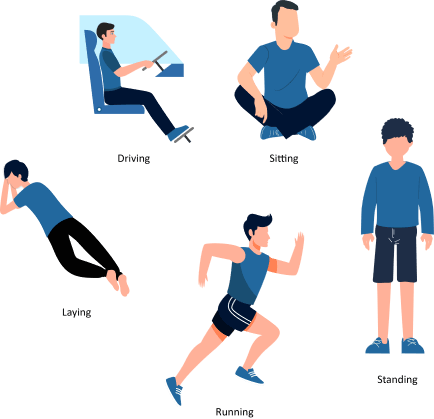

As per definition, a posture can be either static or dynamic. Static Postures are ones in which the body segments are aligned and maintained in certain positions, such as standing, sitting, lying down, etc. Dynamic postures are ones in which the body segments move, such as walking, running, dancing, etc.

Correlating posture with injury history

As a Biomechanist, I’ve learned about posture quite in detail; the theory, the clinical scenarios, the software-based analyses, etc.

The more I learned about it, the more I saw differences in how people talked about posture.

E.g., I once heard a colleague tell their patient, “Your low back pain is because your posture is wrong. Your back is arched more, and your pelvis is tilted forward.” The patient was then given posterior pelvic tilt and spinal flexion exercises.

Like a sudden light bulb, this raised many questions in my mind.

- Has this patient developed an anterior pelvic tilt now, or was it always like that?

- If the patient has always had an anterior pelvic tilt, would it contribute to any pain after all this time?

- Is it that the patient had a “normal” pelvic tilt before, which has now increased to a more anterior tilt? If yes, would such a significant change in the body happen within a short period?

- The colleague had done a visual observation of posture. Can we diagnose increase in pelvic tilt with the naked eye without any quantification?

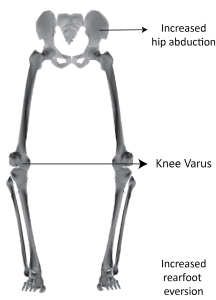

In another instance, I observed an exercise and manual therapy prescription being given to correct the knee varus of an OA knee patient.

- Can we correct a compensatory postural change?

- Is it right to correct a normal compensation done by the body to reduce pain and discomfort just to bring back “ideal alignment”?

Based on these observations, I’ve come up with a theory about the different kinds of posture. This article is wholly based on my anecdotal experiences. Feel free to discuss your views in the comments if your ideas are any different.

I believe that posture can be divided into 4 categories –

- Structural Alignment

- Preferred Posture

- Compensatory postures

- Pathological Postures

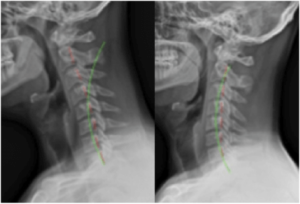

Structural Alignment

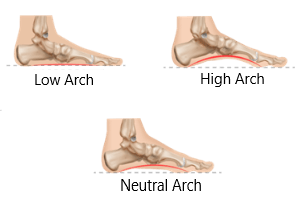

With 8 billion people on this planet, I believe it’s impossible for everyone to have the perfectly aligned knee, prominent foot arches, retracted shoulders, etc. Based on height, weight, activity, and genetics, a person’s body will align accordingly from childhood, and the person will grow into an adult with unique structural features.

Some may have cervical lordosis, and some may have a more neutral-looking cervical spine.

Some may have prominent foot arches, and some may not.

Hence, with a structural alignment, there can be a lot of variability in different people, and this may not be a cause for pain or dysfunction because if the body is set in that way, it’s probably adapted to it over time.

Any changes to the structural alignment happen over a period of time. For example, a hunched-back posture in older people occurs over the course of years, not months.

Preferred Posture

These postures are those that people have complete control over. For instance, we can sit slouched and can sit erect. We can keep our shoulders rounded or protracted at will.

An image showing various types of sitting postures

Preferred postures are the ones people are most comfortable assuming. E.g., you might have heard that sleeping on the stomach is a bad posture. But it would be the only posture they can sleep well in for many people.

Just because someone sits slouched wouldn’t mean that they have thoracic kyphosis. Bearing weight on a single leg while standing wouldn’t mean a person has pelvic obliquity.

The psychological state of a person also affects these postures. A happy person generally is more straightened out, while a sad person is generally slouched.

As long as people change their postures regularly, these wouldn’t be pathological, either.

Compensatory Posture

These postures are generally in response to pain. It is a guarding response by the body to avoid stressing the painful area. For example, In cases of PIVD, a person can have increased lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt to reduce disc pressure.

A trunk list, for example. The spine shifts contra-laterally to the painful side to reduce pain caused by compression.

Similarly, in a Medial Knee OA, with changes in the knee posture, foot pronation occurs to help keep the foot in plantigrade position during weight bearing.

At first glance, it can look like a person presenting with these features has an abnormal posture. But that’s not the case.

Correcting these postures without reducing pain would be meaningless.

Pathological Postures

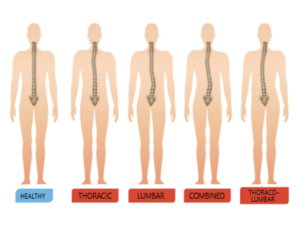

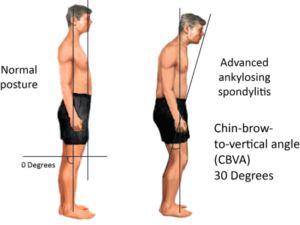

These postures are due to particular pathophysiology. Scoliosis and Ankylosing Spondylosis are classic examples.

An image showing various kinds of scoliotic postures

An image of a person with Ankylosing Spondylosis

These progress rapidly, changing the structural alignment of not only the affected area but also the proximal and distal joints.

Dynamic Posture

As stated in the definition, these are postures in motion. They’d usually be analysed in sport, exercise and lifting ergonomics.

With the same repetitions and movement cues, the same exercise will still look different on different people.

If two people perform squats, the one with longer legs will have a greater forward trunk lean than the one with shorter legs, who will have a more upright posture.

While movement can look largely different in everyone, we should correct dynamic postures in the following instances –

- During repetitive loading. If someone has a manual labour job, correcting their lifting posture to make it more efficient will help reduce overuse injury.

- To maximise efficiency – An overstriding pattern in running reduces long-term efficiency and makes a person prone to running-related injury.

Then what about Posture Analysis…?

With so many varieties of posture, is Posture Analysis even relevant?

In my opinion, it’s applicable for the following –

- Tracking the degree of a compensatory posture.

- Making patients aware about postural problems and to provide visual biofeedback.

- Tracking the progression and correction of a pathological posture.

- Assessing biomechanical faults in dynamic postures.

- Ergonomic corrections/advise for patients.

- Assessing posture for professions in which posture is essential for a career. E.g., Armed forces applicants, models, actors, etc.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

- When does someone’s posture really matter?

- Can we change or correct posture?

- How much time does it take to correct someone’s posture?

Do let me know your thoughts in the comments!

We hope that this blog helped you get a clear understanding of posture and its importance in the world of rehabilitation.

Setting up a posture analysis lab is now easier than ever. To learn more about GaitON’s standing & sitting posture (ergonomics) modules, contact us today!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading our blogs everyday, and each week we bring you compelling content to help you treat your patients better. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — Team Auptimo

The information found within this site is for general information only and should not be treated as a substitute for professional advice from a licensed Physiotherapist. Any application of exercises and diagnostic tests suggested is at the reader’s sole discretion and risk.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

GAYATRI SURESH (PT)

Gayatri Suresh (PT) is a Biomechanist who has completed her B.P.Th from DES College of Physiotherapy and M.P.T (Biomechanics) from SRM College of Physiotherapy, SRMIST. Her field of clinical expertise is in movement assessments through video analysis. Apart from her work at Auptimo, she works as a Clinical Specialist at Rehabilitation Research and Device Development, IIT Madras. She has been conferred with gold medals for her Research presentations and for securing First rank with distinction in her MPT degree respectively