UNDERSTANDING IT BAND SYNDROME IN RUNNERS

IT Band syndrome is the leading cause of lateral knee pain in long-distance runners. To manage it efficiently, it is important to understand the correlation between running biomechanics and its effect on the IT band.

INJURY RATES

- IT Band Syndrome accounts for approx. 10% of all running injuries [1].

- Moreover, females are twice more likely to develop ITBS than males. [6]

- In addition to runners, it can also reduce performance in cyclists, soccer players, field hockey players, basketball players, & rowers [13].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF IT BAND SYNDROME

The exact etiology of ITBS can be multifactorial.

- As per the relatively older friction theory of ITBS, the excessive friction of the distal IT band over the lateral epicondyle of femur due to repetitive flexion and extension movement at the knee is the cause of the pain [1].

- In addition to this theory, Orchard et al suggested the presence of a ‘maximal impingement zone’ found at or slightly below, 30 degrees of knee flexion during foot strike and the early stance phase of running [7] [15]. This can lead to excessive compression of a richly vascularized and innervated layer of fat present between ITB and the lateral femoral condyle.

- The newer hypothesized causative theories of ITBS are related to fascial restrictions, presence of an underlying cyst, or extension of the joint capsule laterally compression of ITB [13].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

- The most common symptom is the insidious onset of sharp pain on the lateral knee while running. The pain typically appears after running a few kilometers and increases in intensity with every mile [8]

- The pain aggravates after running more than 2 miles or hiking more than 10 miles.

- In more advanced cases, symptoms may appear in the first few minutes of an exercise program or may even appear at rest [11].

- Physical activities that aggravate the symptoms include running downhill, taking longer strides, or sitting with a flexed knee for longer duration [11].

- Tenderness can be observed on palpation of the lateral knee approximately 2cm above the joint line. Moreover, the tenderness is best observed in standing and with knee 30° flexed (position of maximal stress for ITB).

- A Mild swelling with ITB thickening at the lateral epicondyle is visible in some cases. Palpation may reveal a sensation of “wet leather” crepitus like that of rubbing a finger on a wet balloon.

- Trigger points can be found in vastus lateralis, gluteus medius, and biceps femoris.

- Studies also link weakness of knee extensors, knee flexors, and hip abductors with the development of ITBS.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Careful history taking and physical examination findings can help rule out other pathologies related to lateral knee pain such as [11]:

- Biceps femoris tendinopathy

- Degenerative joint disease

- Lateral collateral ligament sprain

- Lateral meniscal tear

- Myofascial pain

- Patellofemoral stress syndrome

- Popliteal tendinopathy

- Referred pain from the lumbar spine

- Stress fracture

- Superior tibiofibular joint sprain

DIAGNOSIS OF IT BAND SYNDROME

Mentioned below are some special tests that are useful in examining ITBS in Runners.

1. The Noble Compression test is useful in the confirmatory diagnosis of ITBS. To perform the test:

- Bring the subject into supine lying and flex the affected knee to 90°.

- Secondly, apply pressure at approx. 1-2 cm above the lateral epicondyle while simultaneously extending the knee.

A complaint of severe pain of the same intensity as that experienced when running at around 30° of knee flexion indicates a positive test.

2. The Renne Test is another alternative to the Noble Compression test. To perform the test:

- Ask the patient to stand on the affected leg with the unaffected leg either flexed at knee or simply kept in non-weight-bearing.

- Instruct the patient to perform a single leg squat to 30-40 knee flexion and then come up.

- Repeat the test once more by applying compression force over the distal ITB.

The presence of pain, or crepitus indicates a positive test.

3. The Ober Test is used to assess the flexibility of ITB.

To perform the test:

-

- Position the patient in a side-lying position with the affected extremity facing upwards.

- Bend the affected knee to 90°.

- Slowly abduct and extend the hip so that the hip is in line with the trunk.

- Lastly, lower the affected leg into adduction.

The test is considered positive if the patient experiences difficulty adducting the leg and it remains in abducted position with associated lateral knee pain.

It is important to know that not all patients with ITBS test positive in Ober’s test. Thus, always conduct it with either

Noble or Renne test for a confirmatory diagnosis.

POTENTIAL CAUSES OF IT BAND SYNDROME

Like any running injury, IT Band Syndrome can occur due to any musculoskeletal impairment, training errors, biomechanical faults & extrinsic factors like footwear, etc.

In this section, we will be discussing assessments we can conduct to investigate each of these 4 aspects.

As a clinician, if we can figure out the root cause behind the injury, we can provide effective rehab for ITBS.

PART 1: TRAINING ERRORS LINKED WITH IT BAND SYNDROME

- Usually, less experienced runners with rapid change in mileage, and some strength deficits are at increased risk [3]. A gradual increase in activity can help in minimizing such errors. Training guides like ‘UW Health Sports medicine runners book‘ can be extremely useful to advise training tips to runners.

- Injury rates are usually higher in runners engaged in downhill or slow running. This can be due to the reduced knee flexion angles commonly seen in these activities. A reduced knee flexion not only increases knee loading but also brings the knee angle closer to the impingement zone.

- Moreover, some cross-training activities that include repetitive knee flexion like cycling can also aggravate ITBS [12].

- Runners with a history of ITBS have been shown to use abnormal segmental coordination patterns, which further increases injury risk [3].

- Running on the same side of the cambered road is a common training error linked with ITBS [1] [8].

PART 2: EXTRINSIC FACTORS (FOOTWEAR)

PART 3: BIOMECHANICAL FAULTS LINKED WITH IT BAND SYNDROME

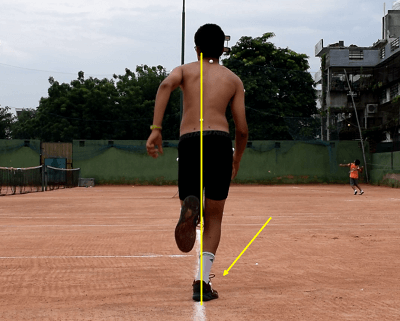

1. CROSSOVER GAIT

Crossover gait is a common biomechanical fault found in runners with IT Band pain. It can be best identified from the posterior view of the runner.

As the name suggests, runners with crossover gait tend to land across the midline of the body.

This reduces the step-width and increases the peak hip adduction & internal rotation angles [10]. To decelerate these hip motions, the distal aspect of the ITB compresses against the lateral femoral condyle, resulting in excessive ITB strain [2].

Crossover gait can often be due to weak hip abductors or excessive dynamic knee valgus. However, it can also be a technical fault done to reduce the net lateral movement of the body.

GAIT RETRAININGS FOR CROSSOVER GAIT

- Step width manipulation: Runners with the crossover sign tend to benefit from step width manipulation, which includes increasing the step width to reduce the overall tibial loads [9]. Verbal cues to run with a wider base of support can also be helpful for runners

- Step rate manipulation: A 5-10% increase in cadence can effectively reduce peak contralateral pelvic drop, hip adduction, and hip internal rotation [4]. This can further reduce the biomechanical demands incurred by the hip in the frontal and transverse planes of motion [2] [5]. For additional retraining strategies for correcting crossover, refer to this link

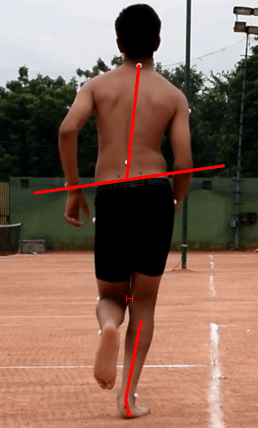

2. CONTRLATERAL PELVIC DROP WITH INCREASED IPSILATERAL TRUNK FLEXION

Altered pelvis and trunk moment patterns are have been commonly linked with ITBS. Any weakness of the hip abductors leads to a contralateral pelvic drop during the stance phase.

The excessive drop creates a shift in GRF, leading to increased knee varus moment & increased tensile strain of ITB.

As compensation for the excessive pelvic drop, runners with ITBS tend to lean their trunk ipsilaterally. This finding is most notable in female runners [6]

CORRECTIVE GAIT RETRAININGS

- Interventions should include strengthening of the lower extremity musculature, even after the symptoms related to ITBS subside.

- Targeting the hip abductor via strength training may benefit both current and previously injured runners with ITBS.

- In addition to a rehab program, visual feedback training to help the runner maintain a level pelvis is very helpful in controlling excessive contralateral pelvic drop. A similar approach can be used to minimize any excessive trunk lean trunk while running [6].

3. EXCESSIVE ANTERIOR PELVIC TILT

A few studies have linked excessive anterior pelvic tilt to runners with IT Band syndrome. This could be due to weak core muscles particularly the rectus abdominis or due to tight hip flexor muscles such as iliopsoas and TFL [14].

Gait analysis is an accurate method to determine the pelvic tilt in a runner [14].

GAIT RETRAININGS FOR CORRECTING EXCESSIVE ANTERIOR PELVIC TILT

Core strengthening programs with an emphasis on rectus abdominis and improving hip muscle flexibility are quite effective in reducing excessive anterior pelvic tilt.

PART 4: MUSCULOSKELETAL IMPAIRMENTS LINKED WITH IT BAND SYNDROME

In addition to training errors, footwear, or technical faults, ITBS can also be due to a musculoskeletal impairment. Such intrinsic factors include:

- Anatomical factors such as increased prominence of lateral femoral epicondyle and leg length differences [1].

- Strength and flexibility deficits: Tightness in ITB or Weakness in gluteus medius [1] [8].

- Increased hip adduction and knee internal rotation is known to create torsional strain in the ITB [6].

- Females tend to be at greater risk due to the greater peak hip adduction angle owing to limited pelvic control in the frontal plane [6].

A detailed musculoskeletal examination helps in understanding if the injury is due to a physical limitation in the body or due to any other factor mentioned above.

MANAGEMENT OF IT BAND SYNDROME IN RUNNERS

Effective management of ITBS involves minimizing friction between the ITB and the femoral condyle and correction of contributing factors.

Thus, the path of treatment is driven by the pathophysiology of inflammation and biomechanics of the ITB strain.

The management is divided into 3 phases: acute, sub-acute and recovery strengthening phase [3] [7] [11]:

1. ACUTE PHASE

The goal of the acute phase is to reduce inflammation. Activity modification and patient counseling is a must in this phase.

- Stop all aggravating activities involving knee flexion and extension. However, cardiovascular fitness training can be continued with swimming using only their arms and a pool buoy

- Use of concurrent therapies like ice, phonophoresis, or iontophoresis can reduce pain and inflammation. NSAIDs are recommended in a few cases.

- Oral, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication is recommended

- Corticosteroid injection, if pain and visible swelling persist after 3 days of the above treatment.

Criteria to progress to the next phase: Up to 2 pain- free weeks before return to running or cycling in a graded progression

2. SUB-ACUTE PHASE

The goal of this phase is to achieve flexibility in the ITB, hip flexors, and plantar flexors as a foundation to strength training without pain.

- Iliotibial band stretching while standing is very effective. Variations include (a) arms at sides (b) arms extending overhead and (c) arms reaching diagonally downwards.

- Moreover, soft tissue mobilization can also reduce myofascial adhesions. Foam Rolling can also help in relieving myofascial restrictions.

Criteria to progress to the next phase: Once ROM is regained and myofascial restrictions are resolved, it is safe to progress to the next phase.

3. RECOVERY STRENGTHENING PHASE

This phase aims at strengthening the gluteus medius muscle including multiplanar closed chain exercises.

New evidence reports that better outcomes can be achieved by combining strengthening exercises with neuromuscular retraining.

- Firstly, perform open and closed chain exercises for gluteus medius with and without resistance (segmental body weight, gravity, and resistance bands). This includes exercises like resisted bridging, resisted hip extension & side-lying hip abduction. Pelvic drops, resisted hip extension, clamshell, lateral band walks, single-limb squat, single limb deadlift, multiplanar lunges, and multiplanar hops are also quite useful.

- For patients with excessive knee varus, visual- feedback can be effective in reducing excessive knee external adduction moments during treadmill walking. Verbal cues such as “bring the thighs closer” and “walk with your knees closer together” while maintaining a normal foot progression angle are also useful.

4. RETURN TO PLAY

Return to running depends on the severity and chronicity of the condition and the patient’s premorbid function.

It’s advisable to resume running only after the patient can perform all strengthening exercises pain-free.

Most patients recover from ITBS within 3-6weeks if they are compliant with their stretching and activity limitations.

- The return to running should be gradual, starting at an easy pace and on a level surface. If the patient can tolerate it without pain, slowly increase the mileage.

- Secondly, cross-training is not recommended in the initial phases. In the first week of returning to play, patients should run only every other day, starting with easy sprints on a level surface. An incremental increase in running volume is recommended.

- Progress to agility exercises and sport-specific drills.

- Lastly, it is equally important to monitor & correct any contributing training errors.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading our blogs everyday, and each week we bring you compelling content to help you treat your patients better. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — Team Auptimo

The information found within this site is for general information only and should not be treated as a substitute for professional advice from a licensed Physiotherapist. Any application of exercises and diagnostic tests suggested is at the reader’s sole discretion and risk.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

DR TEENA ELSA JOSEPH

Dr. Teena is a Sports Physiotherapist who has completed her BPT from Amity University & her MPT (Sports) from Indraprastha University. Her field of clinical expertise in sports & musculoskeletal physiotherapy includes manual therapy, dry needling & myofascial release. Apart from her work at Auptimo, she is also active as clinical researcher in a various of health & sports science research work at Indian Spinal Injuries Center, Delhi. She has achieved several awards for academic excellence along with professional certifications such as Dry Needling (Basic & Advanced), AHA certified BLS provider, NAEMT certified PHTLS provider, IRCS certified Senior professional in first aid, & NIDA certified Good Clinical Practitioner.

REFERENCES:

A-M

- Aderem, J. and Louw, Q.A., 2015. Biomechanical risk factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome in runners: A systematic review Rehabilitation, physical therapy and occupational health. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, [online] 16(1), pp.7–9. Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0808-7>.

- Allen, D.J., 2014. Treatment of distal iliotibial band syndrome in a long distance runner with gait re-training emphasizing step rate manipulation. International journal of sports physical therapy, [online] 9(2), pp.222–31. Available at: <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24790783%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4004127>.

- Baker, R.L., Souza, R.B. and Fredericson, M., 2011. Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Soft Tissue and Biomechanical Factors in Evaluation and Treatment. PM and R, [online] 3(6), pp.550–561. Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.01.002>.

- Bramah, C., Preece, S., Gill, N. & Herrington, L., 2019. A 10% Increase in Step Rate Improves Running Kinematics and Clinical Outcomes in Runners With Patellofemoral Pain at 4 Weeks and 3 Months. The American journal of sports medicine, 47(14).

- Bryan C. Heiderscheit, Elizabeth S. Chumanov, Max P. Michalski, Christa M. Wille, M.B.R., 2011. Effects of Step Rate Manipulation on Joint Mechanics during Running. Med Sci Sports Exerc, [online] 43(2), pp.296–302.

- Foch, E., Reinbolt, J.A., Zhang, S., Fitzhugh, E.C. and Milner, C.E., 2015. Associations between iliotibial band injury status and running biomechanics in women. Gait and Posture, [online] 41(2), pp.706–710. Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.01.031>.

- Fredericson, M. and Wolf, C., 2005. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: Innovations in treatment. Sports Medicine, 35(5), pp.451–459.

- Louw, M. and Deary, C., 2014. The biomechanical variables involved in the aetiology of iliotibial band syndrome in distance runners – A systematic review of the literature. Physical Therapy in Sport, [online] 15(1), pp.64–75. Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.07.002>.

- Meardon, S. & Derrick, T., 2014. Effect of step width manipulation on tibial stress during running.. Journal of Biomechanics, 47(11), pp. 2738-2744.

- Meardon, S.A., Campbell, S. and Derrick, T.R., 2012. Step width alters iliotibial band strain during running. Sports Biomechanics, 11(4), pp.464–472.

N-Z

11. Razib Khaund, M.D Flynn Sharon, H., 2005. A Common Source of Knee Pain. American Family Physician, [online] 71(8), pp.1545–1550. Available at: <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15864895>.

12. S P Messier, D G Edwards, D F Martin, R B Lowery, D W Cannon, M K James, W W Curl, H M Read Jr, D.M.H., 1995. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 27, 951-960.

13. Shamus, J. and Shamus, E., 2015. the Management of Iliotibial Band Syndrome With a Multifaceted Approach: a Double Case Report. International journal of sports physical therapy, [online] 10(3), pp.378–90. Available at: <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26075154%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4458926>.

14. Shen, P., Mao, D., Zhang, C., Sun, W. and Song, Q., 2019. Effects of running biomechanics on the occurrence of iliotibial band syndrome in male runners during an eight-week running programme—a prospective study. Sports Biomechanics, [online] 00(00), pp.1–11. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2019.1584235>.

15. van der Worp, M.P., van der Horst, N., de Wijer, A., Backx, F.J.G. and van der Sanden, M.W.G.N., 2012. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 42(11), pp.969–992.